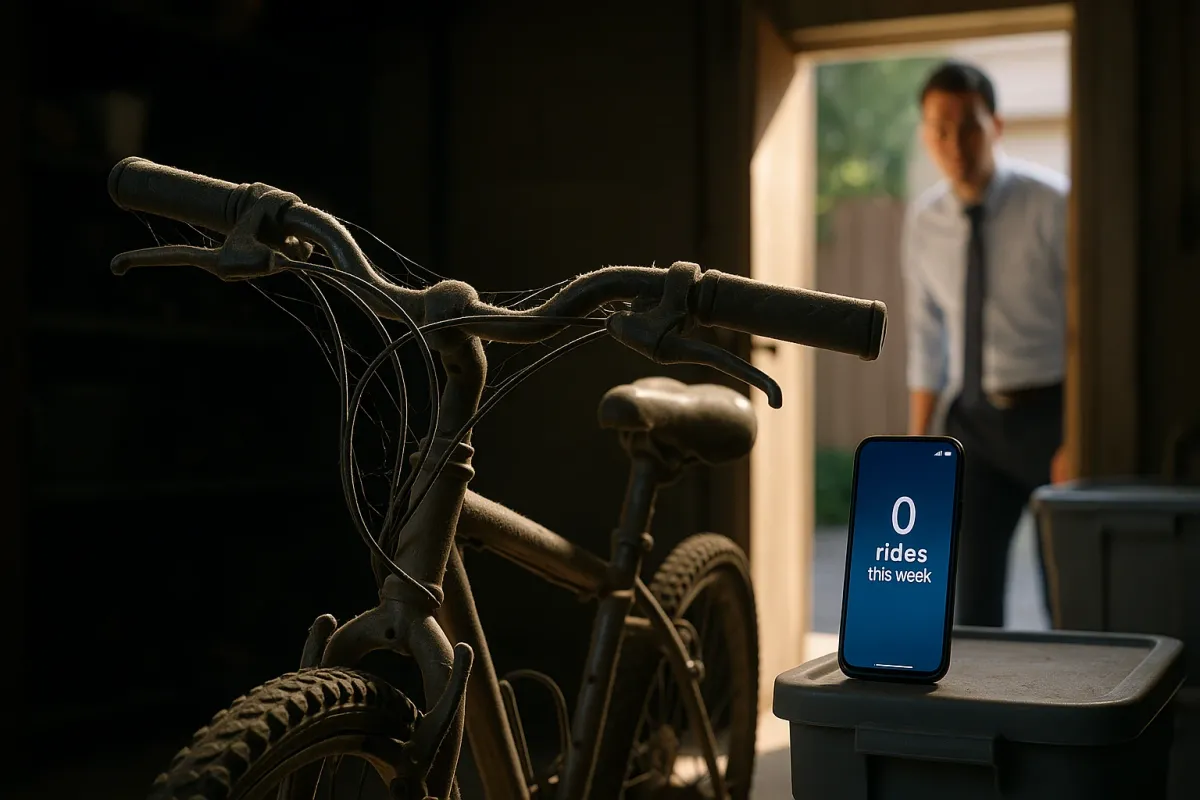

There’s a viral thread doing laps online right now: people sharing the most ridiculous excuses they’d use to call in sick from work. It’s funny—until you realize a lot of riders have been “calling in sick” on their bikes for months. Chain gritty? “Tomorrow.” Brake lever spongy? “Next weekend.” Oil looks like espresso? “It’s probably fine.”

That mindset is exactly how engines die young and brakes fail hard. Your employer might tolerate a fantasy “sick day” once in a while. Mechanical systems won’t. Every skipped check gets logged—quietly, in metal fatigue, varnished oil passages, cooked seals, and toasted pads.

So let’s flip the script. If you can justify a fake sick day for yourself, you can’t justify one for your moto. Here are five brutally practical, technical maintenance disciplines that separate riders who just own motorcycles from riders who deserve them.

---

1. Oil Isn’t a Subscription, It’s a Wear Curve

Too many riders treat oil changes like recurring calendar events—“every 6,000 miles, job done.” That’s the same lazy thinking as “I’ll just call in sick if I oversleep.” Your engine doesn’t care about your schedule; it responds to load, temperature, and contamination.

Key realities:

- **Short, cold rides murder oil faster.** Repeated cold starts without full warm-up mean condensed fuel and water never fully boil off. That dilutes additives and raises acidity. A 3,000-mile winter commuter may need oil sooner than an 8,000-mile tourer.

- **Air-cooled and high-revving engines shear oil quicker.** Spin a small displacement twin near redline for fun? You’re hammering viscosity modifiers. The oil may still “look okay” but have lost film strength.

- **Extended idling is a silent killer.** Oil flows, but airspeed is low, so heat soak climbs. High temps accelerate oxidation and additive depletion.

What to actually do:

- **Shorten intervals if you do lots of cold-start commuting, canyon thrashing, or city idling.** Don’t worship the manual—adapt it.

- **Use an oil that meets the manufacturer’s spec, not just the right viscosity.** Look for JASO MA/MA2 for wet clutches, and the exact API or ACEA class mandated.

- **Watch how the bike sounds and shifts.** Notchy shifting, louder mechanical clatter, and harsher engagement are often early signs your oil’s additive package is fading—change it *then*, not when your odometer tells you.

Treat oil like brake pads: a sacrificial layer. Its job is to die so the metal doesn’t.

---

2. Chain Tension: Why “Looks About Right” Is Mechanically Wrong

Your chain doesn’t care about your eyeballing skills. A few millimeters off spec can radically change how load flows through your countershaft, bearings, and swingarm.

What’s really happening:

- **Too tight:** Every rear suspension compression tries to “pull” the countershaft toward the axle. That adds side load on countershaft bearings and stresses the output shaft. Over time, you get seal leaks, premature bearing wear, and sometimes even end-spline damage.

- **Too loose:** The chain slaps, loads are transferred in sharp spikes, and tensioners/guide rails (where fitted) get hammered. Sprocket teeth see more impact and less smooth meshing, accelerating wear.

- **Dynamic tension matters, not static.** Chain tension is tightest when the center of the front sprocket, swingarm pivot, and axle are in a straight line. Most factory slack specs take this geometry into account—but only if you measure correctly.

Do it the right way:

- **Measure slack at the manual’s specified point.** That might be a labeled spot on the swingarm or the midpoint between sprockets. Use a ruler. Guessing is for people who buy new chains every season.

- **Sit on the bike while someone else measures (if your manual calls for rider-laden slack).** Your weight changes swingarm angle; that changes effective chain length.

- **Adjust in small increments and re-check alignment.** Align via swingarm marks *and* by checking with a chain alignment tool or straight edge from sprocket to sprocket. Marks can be off.

Think of chain slack as valve clearance on the outside of the bike—slightly loose is safe, too tight is expensive.

---

3. Brake Fluid: The “Silent Sick Day” You Keep Approving

Most riders stare at pad thickness and rotor wear, but treat brake fluid like background scenery. That’s dangerous and technically lazy.

What’s going on inside your lines:

- **DOT 3/4/5.1 fluids are hygroscopic**—they absorb water from the air over time, even through rubber hoses.

- That water:

- **Lowers boiling point**, risking vapor lock under hard braking (long downhill, track day, panic stop).

- **Promotes internal corrosion** in calipers, master cylinders, and ABS modulators.

- **ABS systems are especially sensitive.** Contaminated fluid can make valves sticky or slow to respond, triggering strange pulses, warning lights, or delayed intervention.

How to treat it like the critical system it is:

- **Flush on time, not “when it looks bad.”** Color is a horrible indicator; moisture content isn’t visible. Replace every 1–2 years, more often if you ride hard in mountains or track regularly.

- **Bleed from the furthest caliper inward.** Follow the service manual’s sequence, especially on linked or ABS systems. Wrong sequence = trapped micro-bubbles.

- **Don’t mix DOT 5 (silicone-based) with DOT 3/4/5.1.** They’re not compatible unless the system was designed for DOT 5—and most modern bikes are not.

If your lever feel slowly turned from crisp to sponge over months, your brakes didn’t just “have a bad day.” They’ve been calling in sick and you’ve been signing the form.

---

4. Electrical Contacts: The Corrosion You Don’t See Until It Strands You

Everyone loves to talk lithium batteries and fancy chargers, but the real drama often lives in cheap, forgotten connectors. Modern bikes are rolling networks—CAN bus, fuel injection, ABS, ride-by-wire. All of that depends on clean, low-resistance paths.

What kills reliability:

- **Moisture + vibration = fretting corrosion** at connectors, especially on high-vibration singles and twins.

- **Cheap accessory installs** (tapped into the wrong wire, twisted + taped splices, no strain relief) introduce failure points far from factory QA.

- **High current draws** from added lights, heated gear, or phone chargers can push connectors near their thermal limits if not properly specced.

Your countermeasures:

- **Once a season, do a connector audit.** Hit vulnerable spots: battery terminals, starter relay, main ground points, regulator/rectifier plug, ECU connectors, and any aftermarket accessory taps.

- **Clean and protect.** Disconnect, inspect for green/white corrosion, clean lightly with contact cleaner, then apply a thin film of dielectric grease *around* the seal area (not globbed onto pins to the point of hydraulic lock).

- **Check voltage drop, not just battery voltage.** A battery that reads 12.7V at rest can still fail you if you lose 1–2V over a bad ground or corroded connector when cranking. Measure voltage at the battery and at the load under operation; more than ~0.5V drop usually means trouble.

An engine that won’t crank at 6 a.m. isn’t “unlucky.” It’s just been trying to tell you, through slower cranking and dimmer lights, that you’ve been ignoring the system that powers the entire bike.

---

5. Tires Aren’t Just Rubber—They’re Real-Time Telemetry

Tires are the only thing between your bike and the road, yet many riders treat them like background props until they’re visually wrecked. That’s like ignoring your own fever because you’re “too busy” to grab a thermometer.

Technical truths you can’t outrun:

- **Pressure controls carcass behavior.** Under-inflation increases carcass flex, heat, and wear on the shoulders; over-inflation shrinks the contact patch and amplifies harshness and slip.

- **Heat cycles change compound behavior.** A tire repeatedly heated and cooled (track days, aggressive weekend canyon runs) can harden even if tread depth looks fine.

- **Uneven wear patterns are diagnostics.**

- Squared center: too much highway, not enough cornering—no surprise.

- Cupping/ scalloping: often due to weak or mis-set suspension damping, or running too low a pressure.

- One-sided wear: alignment or chassis geometry issue, or consistent riding style (e.g., more right-handers) amplified by setup.

Maintenance, not just replacement:

- **Set pressure cold to the *bike manufacturer’s* spec as a baseline**, then tune based on load and usage. Two-up touring with luggage? You may need 2–4 psi more than solo sport riding.

- **Re-check pressures monthly minimum, weekly if you ride hard.** Air loss happens slowly, but performance loss is immediate.

- **Use the wear as feedback.** If your front tire always cups early, you may need to adjust rebound damping or check fork health, not just blame the tire brand.

Your tires are constantly writing a logbook on how you ride and how your bike is set up. Reading that log is maintenance, not art appreciation.

---

Conclusion

That trending list of ridiculous “call in sick” excuses is funny because everyone recognizes the mindset: procrastinate, justify, repeat. But your motorcycle doesn’t believe stories. It believes torque loads, temperatures, moisture content, and friction coefficients.

Maintenance isn’t about polishing a toy; it’s about respecting a highly stressed, high-precision machine that will give you everything—speed, distance, adrenaline—if you stop treating its early warning signs like optional emails.

Next time you’re tempted to push off an oil change, ignore a lazy chain, or squint at that slightly soft brake lever and think “It’ll be fine until next weekend,” ask yourself one question:

If your bike could call in sick on you, would it?

Don’t wait for the day it finally does.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Maintenance.